Babies and poetry don’t mix. I don’t remember who said that to me, but I remember it being said, and it stuck. The dread it inspired when I started to consider how being a mum and a poet would work still lurks in the back of my brain, and I probably spend more time than I should be worried over the subject. This post isn’t a how-to on balancing motherhood and writing, but it is my personal experience of how I’ve managed those two elements of myself so far. ‘One size fits all’ is almost always a lie, and it’s important that we share our experiences openly and honestly so that others can find the path that works best for them. Parenthood is riddled with judgements, the sense that we’re not doing enough, and that someone is always doing it better. In reality, most of us are doing our best and that is enough. We don’t need to be perfect, we just need to be ourselves. Finding how we do that is sometimes the hardest part.

Before my daughter, the conversation regarding children at poetry events had come up a few times. Opinions were mixed. They ranged from those that felt there shouldn’t be limits on when and where children were welcome, to those who argued that it was unfair on the rest of the audience if parents brought noisy children with them.

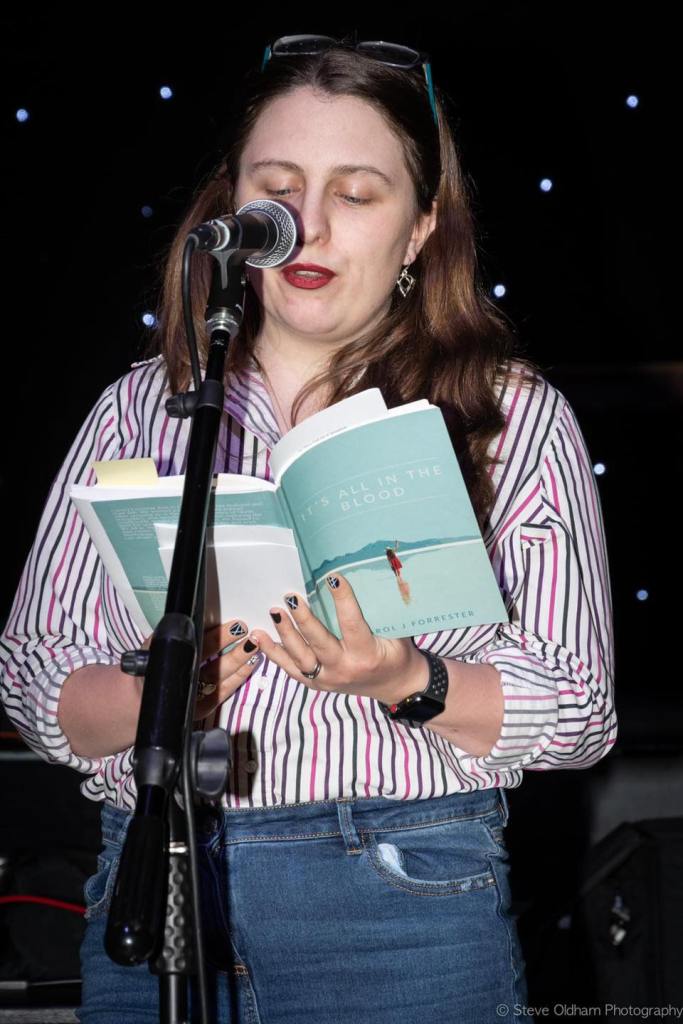

My husband and I had begun discussing having children, and I started to wonder if this was going to mark a pause in my poetry career. My debut collection came out at the end of 2019, and I was planning various readings in 2020 to promote the book. In my mind, I needed to get as much poetry in as I could before I settled down to have a family.

Covid and lockdown struck before any big decisions could be made, and the landscape of poetry events shifted significantly. For a while, it all stopped. Then a few events crept online, and instead of reading to a café, or the back room of a pub, we were reading to squares on a screen. Everything in my life spanned out from my home, and in November 2020 when I fell pregnant with my daughter, it looked as if virtual poetry would be the way in which I could continue reading, and writing.

Virtual events were easily accessible, and low pressure. I could hit the mute button, turn off the camera, and feed my daughter while the poet on the screen performed without messing around with scarves, shawls, or coats. If my turn came and I was caught up with a feed, or a nappy change, I could postpone until later in the zoom call. The noise on my end did not impact anyone but me, and I didn’t have to deal with the rising anxiety of trying to shush an unhappy baby that will not settle, feeling like you are spoiling everyone else’s fun.

Of course, that anxiety was all imagined. I’d not taken my daughter to an in-person event before, and I’d never seen parents doing it so I hadn’t got a real-life example of what poetry and children looked like. I was trying to solve problems that hadn’t presented themselves, and in doing so I both limited myself and put myself under more pressure.

My first in-person event post-lockdown was the Coppenhall Open Mic. At this point, none of the Crewe or Nantwich poetry nights had returned and some are still on hiatus. None of my ‘old haunts’ were running poetry nights, and I found the idea of attending somewhere new a little too daunting. The Coppenhall Open Mic isn’t actually a poetry night. It’s a music open mic, that doesn’t mind poets popping along to join in. I’d messaged ahead to check no one would mind me bringing my poems, (even though I’d been told a couple of poets had performed in a previous month), and worked up the courage to go along.

It was a brilliant night. I have found that when you attend events on your own, it’s always best to find a table with spare chairs and ask if you can join the occupants. I was lucky enough to sit at a table of lovely individuals, and the regulars are incredibly welcoming to newcomers.

I read three poems (though I can’t remember which ones they were for the life of me). What I do remember, is the charge of electricity that I felt from a real, in-person audience, where I could hear the tone of the crowd. Since the rest of the acts had been musical, there had been a level of chatter going on throughout the evening. The moment I took the stage, the room went silent.

It’s a different sort of silence from the enforced mute of Zoom. When I reached a turn in one of my poems, a murmur went through the audience and I was struck with the thought “oh, this is why I keep doing this. This is why I don’t just leave poems on the page.’

As the country opened up, and more in-person events emerged from Covid restrictions, I got braver. I went to Poems & Pints in Macclesfield, I returned to the Coppenhall Open Mic, and I went to a few nights in the Stoke area. Every time I made plans I arranged for a babysitter, and quite quickly I found myself feeling guilty for how much I was relying on family to help watch my child. I felt as if I were being an inconvenience to them, and old anxieties rose up. I felt as if I was treading a narrow path between avoiding my duties as a mother while I went to poetry events, or losing parts of myself to motherhood.

I also saw something I hadn’t before. Another new mum who’d brought her child to the poetry night in Macclesfield, and got up and read while carrying their baby. She had the same concerns about bringing a newborn along as I’d had, and I found myself reassuring her that no one minded his little murmurs and his cooing. I started to consider the possibility of bringing my own daughter along.

Of course, babysitters sometimes fall through. One evening when I’d arranged for a family member to watch my daughter so I could attend the ‘Poetry Blast’ at Queens Park in Crewe, they called to say they couldn’t make it just before I needed to leave. I knew that the café was family-friendly, I’d been there before, and I’d taken my daughter before. The last-minute cancellation of the babysitter meant I didn’t have time to catastrophise what could happen in my head, and I reasoned that home was within a ten-minute jog if things didn’t pan out.

Any parent can tell you, that leaving the house with a child takes three times the preparation compared to leaving by yourself (at least). My daughter had just started weaning, so I had a nappy bag, her tea, a bottle, and what felt like everything apart from the kitchen sink wedged into the pram basket. I arrived red-faced, and out of breath because I’d mistakenly thought the event started earlier than it did. Miraculous, not late, and with enough time to feed my child and get her settled, I introduced her to the world of poetry readings.

It was a good trial run. I knew what facilities would be available ahead of time, and I had friends who were also in attendance. In the second half, my daughter fell asleep, and during the first, she was happy to sit and watch. When I got up to read, a friend held her, and if I’m honest she probably stole the show. No one suggested that I should have stayed at home, or found a replacement babysitter. No one commented on her presence beyond saying hello, and telling me how blue her eyes were. All the concerns that had bubbled away in my imagination stayed in the imagination.

I decided to see how other events would work with her in tow.

When Bryan Dunne put a call out for poets who wanted to take part in an exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery, I put my name forward immediately. I’d visited the art gallery for the first time shortly before his post went up, and I’d fallen in love with the building and the artwork. (Little did I realise, I’d missed half the building on my first walk around.) Bryan’s post also made it clear that the event was family-friendly.

Poets were instructed to pick a piece of art and write a poem inspired by it. Always a sucker for ancient myth, I chose Andromeda and Perseus by William Etty. It was a Saturday event during the morning, and it was also my first experience travelling by train with a baby.

According to the online information, prams are allowed on trains but must be folded up and stored away during travel. This isn’t particularly practical when the pram doesn’t fold as a whole. The one I own has to be dismantled and then folded. Not easy to do on a moving train, with a toddler, on your own. I worked around this problem by taking a baby carrier and strapping my daughter to my chest. I’ll point out that this would not be a workaround for everyone. I’m physically fit and relatively strong. (There’s a story about a trophy engraver that I desperately want to tell, but don’t have the word count to do so in this particular post.) I was able to carry my daughter for the majority of the day, and aside from muscle aches across the next couple of days, I was no worse for wear. For someone with a chronic illness, or a physical disability, carrying a child in a carrier could prove incredibly difficult, if not impossible. There are many reasons why our public transport isn’t fit for purpose for everyone, and this is an area that I feel needs looking at because it sets itself up as another barrier between new parents and their old lives.

Inside the gallery, and in the café with the other poets, I once again found that my worries about attending an event with a baby were unfounded. This time, instead of being mostly silent, my child happily waved at everyone, chatted at whoever looked her way, and blew kisses to the poets as they performed their pieces. When it was my turn to read, I read with her still strapped to my chest. I don’t know if anyone heard a word I was saying over the cuteness pouring out of the small person who thought the audience was there for her, but it was one of the most positive audiences I’ve ever read for.

Talking with the other mothers among the poets, I realised that I wasn’t the only one who felt that motherhood carried an expectation that you put your own dreams on hold. There was a general feeling that poetry events weren’t a welcoming space for mothers with young children. We are expected to raise our kids and then come back to poetry when we were able to give it our full attention. Facilitators like Bryan Dunn (Northern Poets Society), Romina Ramos and Stuart Beveridge (Natter, Bolton) are working hard to build spaces that welcome everyone, but the idea that you shouldn’t take a baby to a poetry night is so entrenched in some of us, that we have to get past our own fears before we can take advantage of those spaces.

Between Manchester, and now, I’ve taken my daughter to various events, and each time I hear the same things. I’m told how brilliant it is that I’m introducing her to poetry so young. I’m told how good she is, and how well she sits through the event. I’m also told how impressive I am for bringing her. I don’t feel impressive when I read with my daughter on my hip (unless she’s really squirming and then, yes, it is impressive that I don’t drop her on the floor). But after the first few readings, I got used to her being there. I made it work, and that is what mothers do, we make the thing work because we don’t have the option, not to most of the time.

I can’t stop writing poetry. It’s a part of me as much as being a mother is part of me. The idea that becoming a parent demands we put our life on hold for eighteen years is not a fair standard to hold anyone to. We should all be allowed the freedom to choose how much of ourselves we give or take, depending on what we feel able to do. I don’t want to just be ‘mum’, so I’m not going to be, but I’m still always ‘mum’ so my daughter has to have a place in what I do. At the Natter event in Bolton, she had just started to toddle around and had the run of the place.

Babies develop so quickly, that each time I think I’ve got the hang of being the mum poet, I suddenly find she’s hit a new stage, and what worked before doesn’t work now. I have to adapt, and I’m not always great at doing that in a calm manner. I’ve been lucky that the poetry circles I’ve found myself in are filled with people who believe that art spaces should be open to all, and follow through on that belief. While I was apologising for the eighteen-month-old determined to crawl over and investigate every inch of Th3Guys café in Bolton while the poets were on-stage, everyone else was delighting in her. A couple of weeks later I was chatting to some people from a zoom open mic and someone said “oh you’re the one who had the baby at Natter! She was brilliant!”. What could have been a night where I decided not to continue taking my daughter to events, turned into a reason to keep taking her. The week before last I ran into a poet I’d met briefly in December who’d brought their wife, and eight-week-old to the poetry night we were both at.

He told me he was following my example, which might have been a joke, but it was a good reminder that we need examples from time to time. I needed to see someone else get up and read while wearing their baby, to risk attempting the same. It’s why I post photos of my daughter and me at events on social media, and why I’ll keep taking her to readings, even if I spend more time following her around the room than sitting in my seat. I’m still part of the poetry community, and they’ve made it clear that both my daughter and I are welcome. Taking advantage of that isn’t selfish, it’s self-care.

Organiser and Events Mentioned In This Post:

For a list of monthly events located in the North-West and Midlands area – check out my post on that very topic:

[…] I’ve posted about my concerns regarding taking my daughter to poetry events, and how they might overtake my identity as a poet. I worry that I may become the ‘mum poet’ rather than just a poet. I think this same concern made me hesitate each time I started to write a poem about my pregnancy, and then about the birth. Even now, I can count the number of poems I’ve written about being a mum on one hand. Sitting down to write about those experiences still proves to be a challenge for me. […]

Reading this post made me so so so so soooooo excited and proud of you for taking the initiative to literally be the leader for so many mothers/parents in the poetry community. You’ve started a revolution.

One of the reason why I love reading poetry is that, from time to time, I come across a poem where the poet does something that is not usually done in poetry or that I am not accustomed to. In moments like that, I find myself amazed, “….wait a minute…I can do that? Omg I’m allowed to do that in a poem!” You’ve allowed every parents in the poetry community to have this reaction.

Thank you for sharing this post. Best of luck to you, your wonderful daughter, your family, and—of course—your poetry career ✨